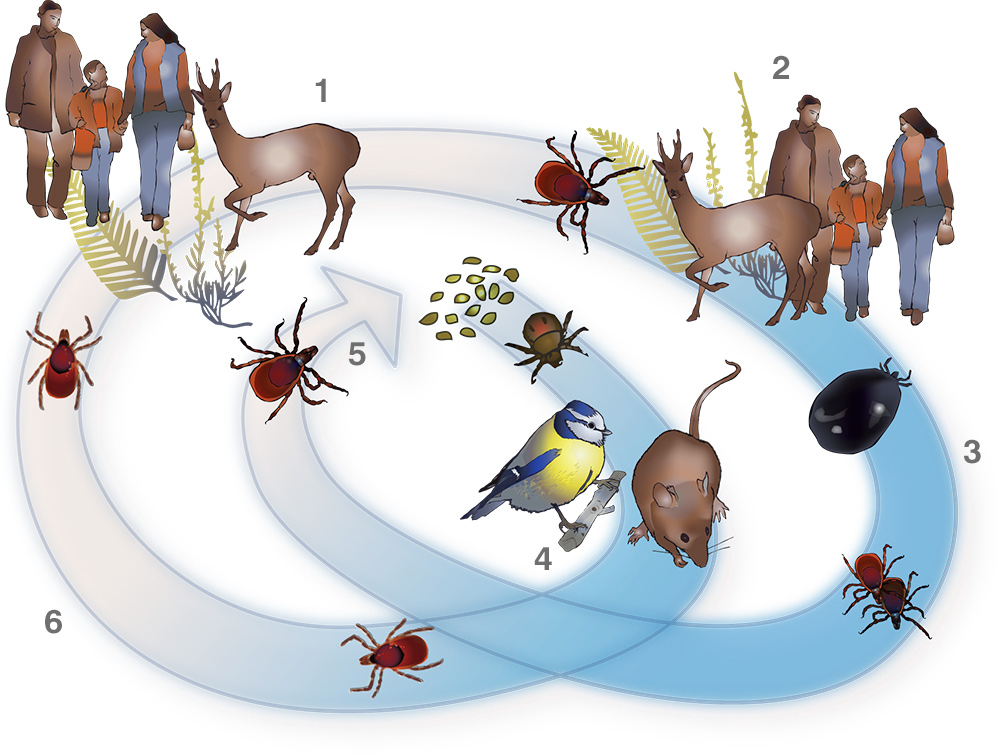

1: (Summer) after feeding on blood the nymph drops off the host and matures into an adult; 2: adults find their tertiary hosts: deer, humans, dogs etc; 3: (Autumn) after feeding an adult is enlarged out of all proportion to its original size; adults mate and eventually fall off the host; 4: ( Winter) larva use mice and birds as their first host, fall off, become nymphs and go dormant for six months; 5: at two years old the adult females lay eggs; eggs laid in spring, appear as larva during the spring/ summer; 6: (Spring) the dormant nymph wakes in spring and finds a secondary host in deer, humans and other mammals

Aim

The aim of this guide is to raise awareness of Lyme disease and methods of prevention.Cause of Disease

Lyme disease is caused by a spiral-shaped, spirochaetal bacterium of the Borrelia genus. There are hundreds of strains of Borrelia bacteria, many of which remain unstudied. Lyme disease (also termed Lyme borreliosis or Borreliosis) is spread to humans (and other mammals and birds) through the bite of infected ticks.

In the UK, there are two families of ticks, hard ticks and soft ticks. It is usually hard ticks that spread Lyme disease. The most common ticks to transmit Lyme disease to people and companion animals in the UK are Ixodes ricinus (also known as the sheep tick, deer tick, wood tick, and castor bean tick) and Ixodes hexagonus (the hedgehog tick).

Both these hard ticks have several life-stages (see illustration). From hatching, the larval ticks seek a host (this is termed ‘questing’), which involves waiting on low vegetation, forelegs outstretched. The tick can sense chemicals, heat and movement from a passing host. As the host brushes by, the tick latches on with special hooks on its legs. It then proceeds to search for suitable feeding site.

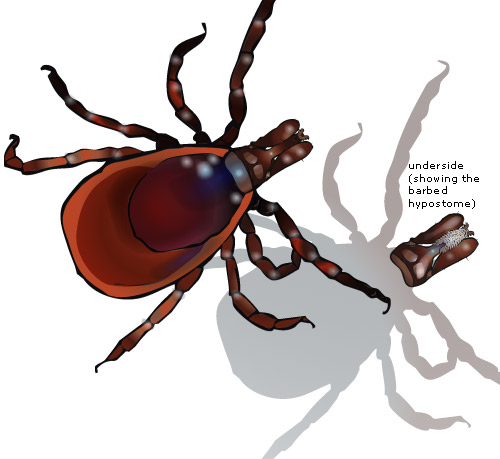

The mouthparts of the tick comprise 2 chelicerae (cutting tools), 2 palps (limbs with sensory organs) and a hypostome, which is a barbed tube that anchors into the flesh of the host. Blood is then drawn up the tube into the body of the tick. The mouth parts can vary in size and shape depending on the species of tick.

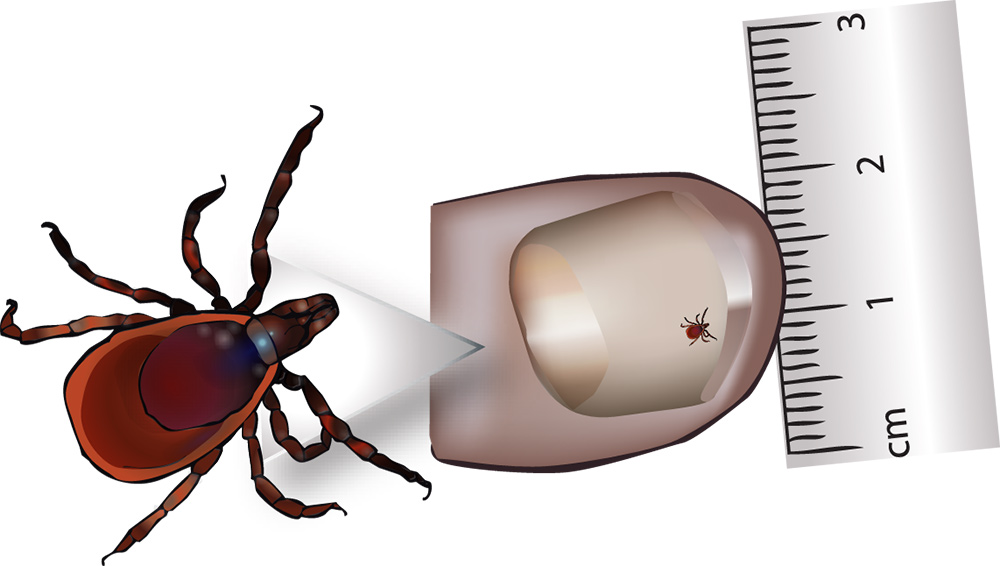

measured on a thumb, the nymph is 2mm

The tick’s saliva contains a number of bio-chemicals which have anaesthetic, anticoagulant, anti-inflammatory and, in some species, adhesive properties. These help to allow the tick to feed without discovery and to keep the blood flowing. It is during the feeding process that the tick ingests Borrelia bacteria and other pathogens from an infected host. Once fed, the tick leaves the host, and either moults to the next life-stage, or in the case of an adult female, lays a batch of many thousands of eggs before dying. Each time the tick feeds on a new host, it is able to transmit the Borrelia bacteria and other pathogens into the bloodstream of that host.

Only a percentage of ticks carry Borrelia bacteria, however, this percentage can vary from area to area. Prompt removal is important, as the risk of infection increases the longer the tick remains attached. Checking for attached ticks regularly will help to reduce the risk, and will increase the chances of discovering them before they have had time to attach.

Mouthparts (from above): two palps cover the hypostome, while two chelicerae are used to cut through the skin of the host. (from below) the barbed hypostome

Larval and nymph ticks are tiny (even when engorged) measuring between 0.5mm and 1.5mm (as small as a poppy seed) and so can be difficult to see; therefore disease transmission is more likely to occur if they remain undiscovered.

Apart from through tick bites, it is also possible for Lyme disease to be passed from a mother to her unborn baby. Borrelia bacteria have been isolated from various body fluids and tissues, and from other arthropods. However, to date there has been no scientific study to investigate these as potential means of transmission.

Other pathogens can be carried concurrently by ticks. Some of these pathogens can be transmitted in other ways, such as through blood transfusions. As ticks can carry a cocktail of organisms, it is useful for a doctor to check for these co-infections.

Correct tick-removal techniques are vitally important in avoiding transmission of infective organisms. Freezing, burning or smothering ticks with substances such as petroleum jelly, alcohol, butter/oils, aftershave etc, can cause ticks to regurgitate their stomach contents back into the host. Scratching off or squashing/crushing an attached tick can also spill the stomach contents and leave mouthparts embedded in the skin. Refer to the “Removing embedded ticks” section for instructions on safe removal.

Signs & Symptoms

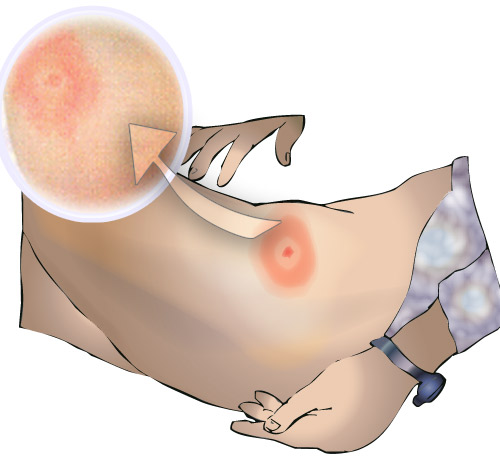

The bite from a tick tends to cause a lump on the skin with a small scab. They are not usually itchy or painful, and so may easily be missed. The earliest, most common, and in some cases only manifestation of Lyme disease is “erythema migrans” (a pink or red rash spreading from the site of a tick bite), which appears approximately 3-30 days after a tick bite. However, atypical rashes also occur and may be dismissed as an allergic reaction, fungal infection or other skin complaint. It should also be noted that some studies have demonstrated that less than 50% of Lyme disease patients present with a rash at all.

Other common symptoms with early infection may include “flu like” symptoms such as joint and muscle aches, stiff neck, fever, headaches, swollen glands and tiredness/fatigue. Apart from the distinctive erythema migrans, none of the early symptoms are unique to Lyme disease, which may make diagnosis difficult. If left untreated, early symptoms may persist for weeks or longer and dissemination of the disease may lead to more serious complications, such as a viral-like meningitis, facial palsy, other nerve damage or arthritis. All stages of the infection usually respond to treatment with antibiotics, but it is easiest to treat at an early stage, especially when the rash is present.

More rarely, persistent and recurrent symptoms can occur, in some cases months or years later. However, especially in the case of people whose occupation or hobby places them at high risk of tick-bite occurrence, re-infection should also be considered.

Neuroborreliosis (infection of the nervous system) is the commonest complication of Lyme borreliosis in the UK. Lyme arthritis is rare in patients with UK-acquired infection, but more common when the disease is acquired in North America or some parts of Europe.

Some patients may go on to develop a post-infection syndrome, termed “Post-Lyme Syndrome”, which apparently occurs when immunologic mechanisms are triggered by the infection. Differentiating treatment failure from “post-Lyme syndrome” is difficult, because they have both been poorly defined. However, it is generally agreed that a true treatment failure means ongoing infection, that is, the presence of live Borrelia burgdorferi. By contrast, “post-Lyme syndrome” consists of residual symptoms lasting for many months after therapy without evidence of the bacteria.

- Ensure you are familiar with the early symptoms of Lyme disease

- If symptoms appear following a bite or exposure to a tick environment and you suspect infection of Lyme disease, seek early medical treatment.

- Ensure the doctor is aware of any tick bites or exposure to ticks.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is easiest when there has been a known tick bite, followed by the characteristic erythema migrans. Unfortunately many people are not aware that they have been bitten, which, in areas where the incidence of the disease is low, may lead doctors to misdiagnose. Additionally, the lack of a rash, or an atypical rash, may also result in Lyme disease being overlooked as a potential cause of a patient’s ill health.

To aid diagnosis, it is advisable to photograph any rashes and to keep any ticks after removal for identification purposes. Write the date of the rash occurrence on the photograph. To keep the tick, write the date of removal in pencil on a piece of paper and place it with the tick in a plastic bag. Put the bag in the freezer. To dispose of the tick at a later date, throw the un-opened bag on the fire or dispose of it in the dustbin. Do not handle the tick with bare hands, even if it is dead.

Lyme disease should be diagnosed by a physical examination and medical history. This clinical diagnosis may in some cases be supported by laboratory testing. Blood tests are typically useful only after two to six weeks following infection, as they test for antibodies (the body’s immune system response to infection), which takes some time to develop. Antibody tests are useful but not infallible. A few patients may have Lyme disease without the presence of antibodies (seronegative), often because of early antibiotic treatment. The serodiagnosis of late Lyme disease requires good, specific clinical histories, and with some patients there may need to be a trial of treatment.

- Lyme disease acquired at work is a reportable occupational disease under the Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations (RIDDOR) 19951,2.

Lyme disease is a notifiable disease in Scotland and doctors are required to report suspected cases.

Treatment

Antibiotics form the mainstay of treatment for the early manifestations of Lyme disease, and are effective at preventing the later symptoms. Later stage infections also respond to antibiotics, but recovery may be slower. For most patients the long term outcome is good. There is currently no vaccine for Lyme disease.

Prevention

Preventing tick bites is the most effective way of avoiding Lyme disease.

Tick bites are most likely in spring, early summer and autumn; however, ticks may be actively questing from 3.5°C and can be active all year round.

- Avoid walking in areas of cover such as woodland, moorland, long grass or bracken, and walk in the centre of paths, where possible.

Cover exposed skin with long trousers tucked into socks (or use gaiters) and long sleeved shirts with cuffs fastened. Elastic or drawstrings at the cuff, trouser-leg and waist band can prevent ticks from crawling under clothing.

Insect repellents can help, especially if applied to the naked skin. Repellents that contain 25-50% DEET are effective at repelling ticks. These may need to be re-applied and should not be used over large areas of the body. Always follow the manufacturers’ guidelines.

Clothing can be sprayed with insect repellent or permethrin insecticide. Permethrin-impregnated clothing is also available from specialist outlets. However, for households with pet cats, it should be noted that permethrin is highly toxic to cats and they should not be allowed to come into contact with treated clothing.

Ticks can live for a long time in clothing so brush off clothes before going indoors as a precaution. In tick infested areas consider carrying a spare change of clothing to be worn for traveling home in.

Examine for ticks every three to four hours and at the end of each day spent in a tick habitat. Pay particular attention to skin folds, e.g. the groin, armpits and waistband area and areas with thick body hair, as well as behind the ears and on the scalp. Check children thoroughly as they tend to play with the outdoor environment as well as in it.

Flea/tick collars or products such as Frontline will help to protect pets from ticks. Seek veterinary advice as some products that may be suitable for one type of animal may be harmful to another.

Removing embedded ticks:

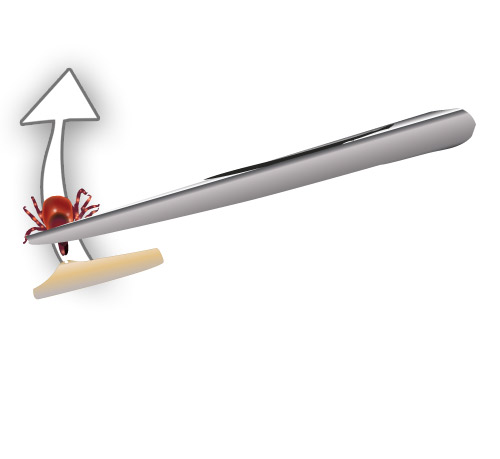

to remove hold tweezers firmly and use constant pressure to pull tick free of skin

The aim is to remove all parts of the tick’s body and to prevent it releasing additional saliva or regurgitating its stomach contents into the bite wound.

- Remove ticks as soon as possible.

Do not apply cleansing agent to the tick as this may stimulate it to regurgitate its stomach contents into the host.

Do not attempt to freeze or burn the tick off or use any substance to remove it.

Use a tick removal hook or fine-tipped forceps/tweezers and wear plastic gloves or shield fingers with tissue / paper. Grip the head of the tick as close to your skin as possible.

If using forceps / tweezers, pull steadily upwards, taking care not to crush the body of the tick. If using a tick-removal hook, follow the manufacturers’ instructions.

Do not squeeze the body of the tick as this may cause it to regurgitate its infected stomach contents.

If any parts do break away and get left behind in the skin, a magnifying glass and a sterilized needle can be used to remove the remaining bits. The bite area should be checked regularly for any signs of localized infection or an allergic reaction.

Wash hands thoroughly afterwards with soap and water.

Seek medical attention if any symptoms occur or any complications arise from the bite site.

Keep the tick for later identification (as detailed previously) to aid diagnosis.