Aim

The aim of this guide is to provide information on factors to consider and signs and symptoms to look out for when assessing the health of wild deer.

Introduction

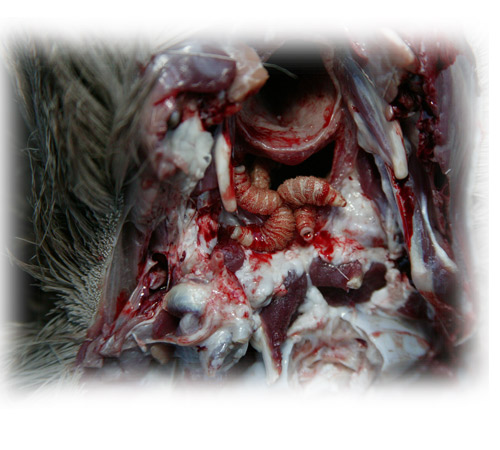

mesenteric glands very badly swollen

Maintaining healthy wild deer populations is important for deer welfare as well as reducing the potential risk of disease transmission to humans, livestock and other wildlife species. Whilst infections of parasites and diseases of deer are unlikely to affect deer management activities directly, early diagnosis of and prevention of infections by practitioners may play an important role in the management of infections, particularly those with implications for human health or livestock production.

The ability of practitioners to monitor and assess deer health in both living and shot deer is important for two reasons the production of venison as a food product and the reporting of notifiable diseases. Wild deer health is also important for the revenue associated with stalking, venison and tourism.

Recognising ill-health

mediastinal lymph node with abscesses

Disease can be defined as an abnormal condition interfering with the animals functioning and can usually be recognised by symptoms (in a live deer) and signs of illness (in the carcass). Wild deer tend to be remarkably free of disease.

- Ensure that you are familiar with and can recognise symptoms and signs of ill-health in deer. Recognising ill-health requires an understanding of what is normal and therefore what is abnormal.

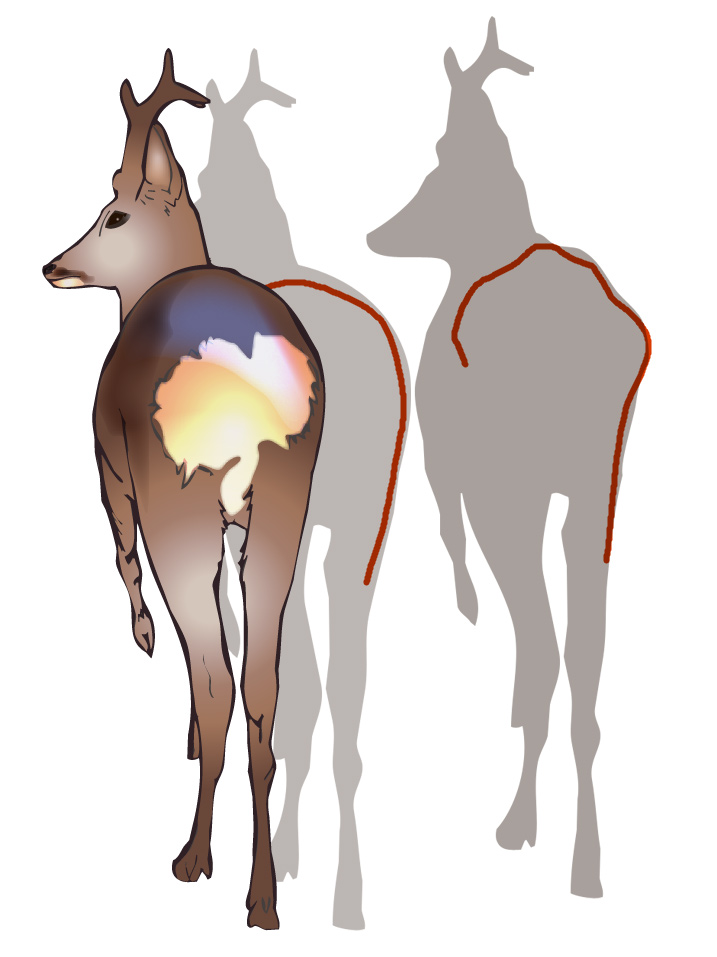

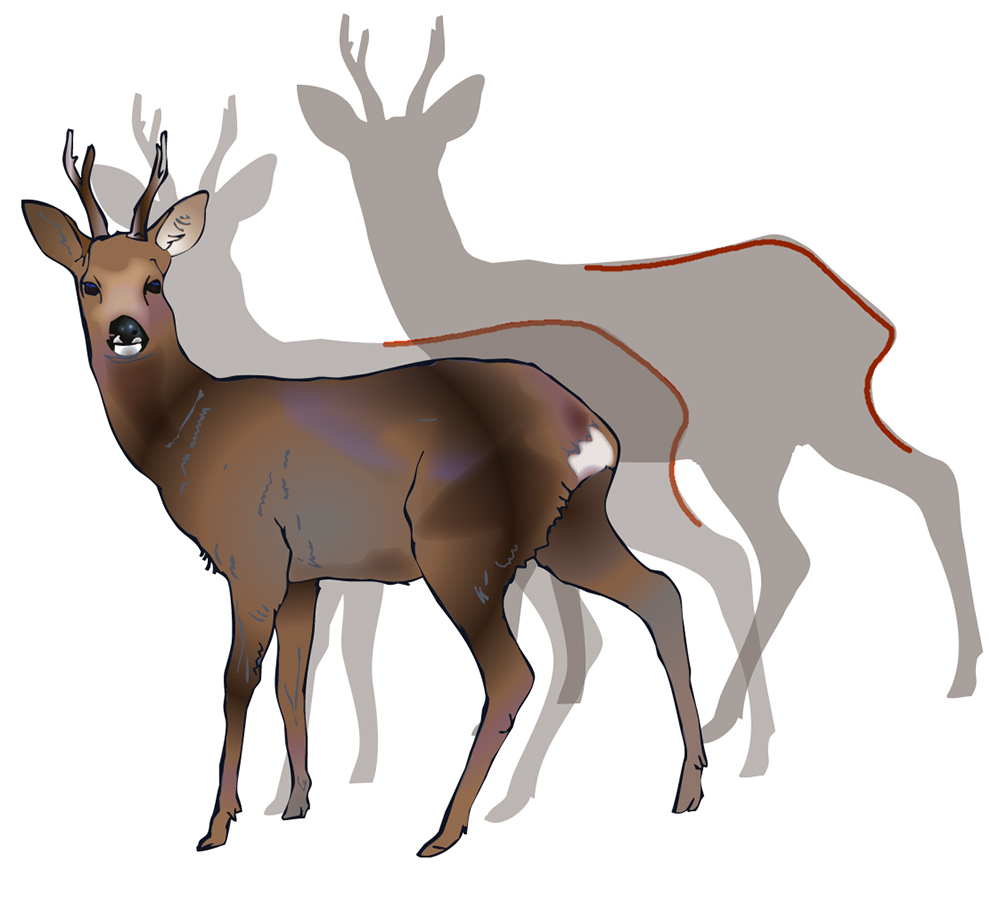

Good Condition (left) Poor Condition (right)

The following are useful indicators:

Changes to normal behaviour

- Leaving the group and grazing alone (for herding species).

- Cessation of feeding and cudding.

- Loss of balance.

- Collapse or apparent paralysis.

- Repetitive walking in set patterns.

- Walking into obstacles, inability to jump easy obstacles or run for any sustained distance.

- Repeatedly getting up and lying down again.

- Teeth grinding and/or heavy salivation.

- Head shaking.

Good Condition (left) Poor Condition (right)

Body Condition

Poor condition:

Body contours around the lower back and rump are angular and concave Rib and pelvic bones may be protruding and visible through the skin. Loin and rump muscles thin with little fat cover

Good condition:

Body contours, particularly around lower back and rump are full, smooth and rounded Loin and rump muscles are full and have thick fat cover

Deer are best able to tolerate/resist diseases and parasites when they are in good body condition.

Disease may affect the body condition of deer. Body condition can be visually assessed at a distance. Visually the best guide to condition is the profile of the hindquarters. Animals in poor condition tend to show projecting pelvic bones and wasting of the haunches. The ribs may also be visible and neck and shoulders may appear scrawny in poor condition animals. The stomach can also appear bloated and the rear-end soiled.

Time of year and breeding condition of the deer must be taken into account - an animal which might be considered in good condition if seen in the spring would be thought thin if seen in similar condition in August, while a lactating hind might be thought thin when compared to one which has lost its calf or is yeld.

- The ability to recognise poor body condition throughout the year in different stages of coat moult is important.

Poor condition: Body contours around the lower back and rump are angular and concave. Rib and pelvic bones may be protruding and visible through the skin; Loin and rump muscles thin with little fat cover

Good condition: Body contours, particularly around lower back and rump are full, smooth and rounded. Loin and rump muscles are full and have thick fat cover

Coat Condition

A poor or ‘staring’ coat (except during moulting periods) may indicate poor condition due to heavy parasite infection or other disease, as may retention of winter coat long after deer of similar age have moulted.

Faeces

Diarrhoea (scouring) or soft faeces may be a sign of disease (e.g. Johne’s disease), or of high intestinal parasite levels.

Swellings and lumps

Those occurring on legs often result from a healed or healing bone fractures. ‘Angleberries’ (benign papillomata) may be found on the body but are uncommon and not serious.

The following symptoms and signs may also indicate disease:

Other symptoms (live deer)

- Unusual secretions from mouth, nose, anus etc.

- Deformed antlers/animals in velvet at an unusual time of the year.

- Lameness (most lameness will result from injury rather than disease but some diseases e.g. Arthritis and Foot and Mouth Disease may present as lameness).

Other signs (carcass)

-

- Lymph nodes swollen and/or abscesses present (see carcass inspection and humane dispatch ).

- Fluid filled swellings in body cavities or under the skin.

- Swellings, lesions, lumps, deformities or other abnormalities of bones, joints, organs or body tissue.

- Abnormalities in smell, colour, shape or texture of organs and tissue.

- Adherence (sticking) of internal organs to chest wall (pleurisy) or abdominal wall (peritonitis).

Parasites

Wild deer can have a wide range of internal and external parasites. The most common internal parasites are lungworms, liver fluke, gastro-intestinal worms, warble flies and nasal botflies, with ticks, keds, lice and warbles the most common external parasites. Of these, the most serious in terms of deer health and welfare are:

- lungworm in all deer;

- liver fluke in roe deer;

- warble fly in red deer calves.

Botfly larvae present in nasal cavity

Treatment using drugs and humane dispatch

Treating disease with veterinary drugs is generally not recommended and there are a number of legal obligations which must be observed if wild deer are to be medicated. To relieve suffering in a diseased deer, humane dispatch )

should be considered as the recommended course of action.

- Ensure that any wild deer treated with a licenced pharmaceutical is clearly marked to prevent the carcass entering the food chain if it is shot.

- Relieve suffering by dispatching the deer humanely (this may legally take place at any time of year, time of day or using any method - under Section 25 of the Deer (Scotland) Act 1996).