Aim

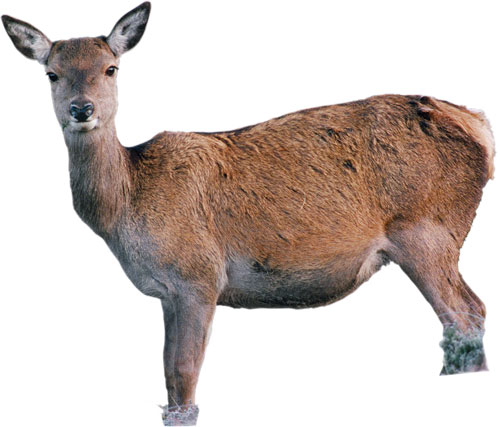

red hind in winter coat which has a ‘bleached’ appearance

The aim of this guide is to provide information on aspects of the ecology and behaviour of Red deer to aid in the management of this species.‡ Red deer are a truly native species, present since the Ice Age.

Social structure

Adult males and females are typically sexually segregated for most of the year, occupying different areas of their range and generally interacting only during the rut.

Group size varies. Female groups tend to be matriarchal and led by a dominant female. She becomes obvious as the leader when the group is disturbed and moving. Generally, young hinds remain with their mother’s group; young stags disperse to group with other bachelor males.

Body condition changes

Winter: Rate of loss governed by weather conditions, food quality and quantity and shelter availability. Lactating hinds lose more condition relative to yeld (females without calves) hinds. Stags are in poor condition after the rut.

Spring: Early spring is period of peak mortality, especially stags, particularly if spring flush of vegetation is delayed. Condition is regained from spring flush of vegetation.

Hinds

Breeding

Single calf: Born in May (woodland) and June (open range). Very exceptionally, twins born.

Productivity: Directly influenced by food and shelter.

Woodland − hinds commonly pregnant after second rutting season. Generally a calf is produced annually thereafter

Open range − hinds more commonly pregnant after third rutting season. Thereafter, hinds may only produce a calf every second year.

calves are spotted at birth but lose these in their first year

Weaning of calves: At 4 months. Calves may continue to suckle beyond this period but are not dependent on milk.

Calving behaviour: Hinds break away from group to give birth rejoining only when the calf is strong enough to run with the herd. During the first few days, the calf is left alone between suckling bouts. When strong enough to run at foot, will join the rest of the herd.

Vocalisation: Hinds may bark when alarmed and moo when looking for their young.

Shoulder height: 1-1.2 m

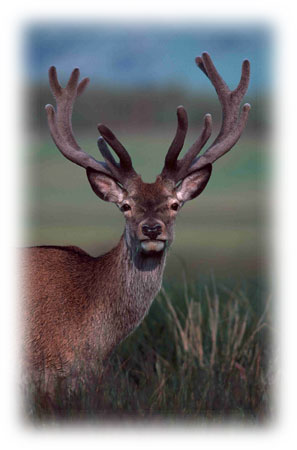

Mature stag in summer coat and antlers still in velvet.Summer coat: bright red-brown. During summer, ridges may provide a breeze to escape from insects. Where flies are not a problem, deer rest up in sunny sheltered areas

Stags

Antler development

Mid Mar − Jul: Antlers cast (older and better condition stags cast first).

Jul − Sept: Antlers harden and ‘velvet’ dies.

Aug – Oct: Antlers clean of velvet.

Mating

Sept: Stags ‘break out’ of bachelor groups to find and claim groups of hinds as the hinds start to come into oestrus.

Late Oct: The peak of the ‘rut’ normally occurs during this time, but may extend into Nov.

Vocalisation: A deep, low bellow or roar plus grunts.

Shoulder height: 1-1.3 m

Calves

Social dependency: Calves remain with their mother as yearlings, learning her home range during this period. Social groups of a hind, her calf, and yearling are common.

Social structure

Adult males and females are typically sexually segregated for most of the year, occupying different areas of their range and generally interacting only during the rut.

Group size varies. Female groups tend to be matriarchal and led by a dominant female. She becomes obvious as the leader when the group is disturbed and moving. Generally, young hinds remain with their mother’s group; young stags disperse to group with other bachelor males.

Body condition changes

Winter: Rate of loss governed by weather conditions, food quality and quantity and shelter availability. Lactating hinds lose more condition relative to yeld (females without calves) hinds. Stags are in poor condition after the rut.

Spring: Early spring is period of peak mortality, especially stags, particularly if spring flush of vegetation is delayed. Condition is regained from spring flush of vegetation.

Summer: Unless aged or in poor health, fat reserves are being accumulated.

Autumn: Stags stop feeding during the rut and rapidly lose condition.

Compared to sheep and cattle, deer have a relatively poor insulative properties. Their behavioural strategy therefore is to seek shelter. Where shelter is deprived or not available this could create a welfare issue

Patterns of activity

Habitat and range

Woodland edge provides ideal habitat, however the species has adapted to life on the open hill throughout much of Scotland. Woodland residents are generally larger than those on the open hill due to access to better quality food and shelter.

‘Hefted’ hinds remain in a limited area of their available range throughout their lives and rarely move further than 5 km from their birth place.

Stags range over much larger areas, and may move up to 40 km throughout the year.

Feeding

Both sexes graze and browse a wide variety of plants (grasses, heather, shrubs and trees), depending on the time of year and availability. Hinds, being smaller, tend to feed on higher quality grasses and herbs, whereas stags can utilise poorer quality forage in greater bulk. Feeding tends to occur in bouts at intervals of about three hours, after which deer ‘lie up’ to ruminate.

Daily movements

In woodland, red deer are generally crepuscular, feeding mostly at dawn and dusk. In open-range deer, diurnal movement patterns may be observed within home ranges, i.e. groups going from high to low ground at dusk and returning at dawn. Opportunities to encounter deer significantly increase during these times.

Seasonal movements

Sept/Oct: Stags rutting; their location is governed by the location of the hinds.

Nov − Apr: Stags congregate on lower wintering grounds. Hefted hinds on open range remain on the high ground until pushed onto lower ground by poor weather or food shortage.

May/Jun: Stags and hinds seek out the first flush of grass, often showing significant changes in foraging patterns.

Jul/Aug: Stags are in good condition and need to range less to feed, due to food availability.

Response to weather

Red deer tend to graze whilst moving into the wind. Periods of strong wind from one direction may move deer to the furthest extent of their range in the direction from which it is blowing.

Response to humans

Deer may learn to recognise and respond to human behaviour and sounds that they associate with danger.

Responses include:

- Increased wariness relating to culling activity;

- Grouping into larger herds which are more difficult to approach undetected. Impact on habitat can become concentrated in certain areas;

- Deer become increasingly nocturnal.

With this in mind, practitioners should ensure that the short-term gains in terms of numbers of animals culled per day does not compromise the efficiency of longer-term deer control.

Damage

Mar – May: Where they have access, deer are more likely to ‘maraud’ onto improved grazings.

Aug/Sept: Fraying by males occurs (the main damage impact of deer in woodland and recognition of cause ).

- ‡Ensure you are familiar with the annual cycle of both males and females to ensure that management activities do not compromise animal welfare. For example be particularly aware of times of the year when: •Females may have calves at foot •Offspring may be dependant •Non-target animals may be in poor condition and be affected by disturbance.